By Darcia Narvaez, EvolvedNest.org

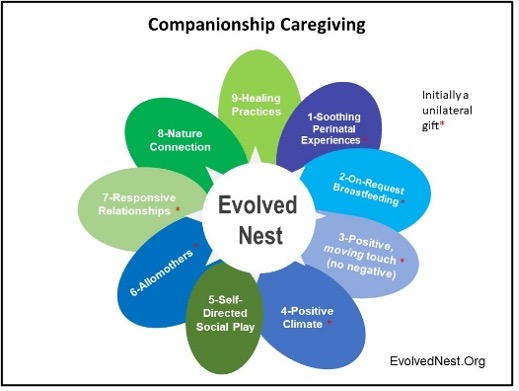

It is becoming increasingly clear that the developmental system our species evolved is critical for fostering our fullest capacities. I call this the evolved nest, for short. We’ve been gathering data and compiling research on the components for over ten years (see here).

When we observe the people in societies who provide the evolved nest, we can see that although their physical challenges can be high, they are stronger, more perceptive and happier than people in societies where the nest is degraded.

One type of society that provides the evolved nest represents our ancestral context; that is, we spent 95% of our species’ existence as small-band, hunter-gatherers or nomadic foragers. Found all over the world, they share particular common characteristics. They live in cooperative bands of kin and non-kin of 5-25 people, with next to no possessions. The groups are fluid, shifting from day to day, but individuals are generous in sharing, and are fiercely egalitarian—teasing relentlessly anyone whose ego inflates, until it calms down. They are highly communal but also highly autonomous. Individuals do what they feel like; no one is coerced, not even children. All humans today can trace their ancestors to one nomadic foraging group, the San Bushmen of southern Africa, a culture that is perhaps 200,000 years old. Although we cannot and do not want to return to their way of living, they give us insight into human development and fulfillment, and why we have so much mental and physical illbeing.

We can observe from these societies that the evolved nest fosters a well-functioning neurobiology, starting with the self-regulation of multiple systems. They grow deep sociality and capacities for getting along with others, including non-humans. The children turn into thriving adults who display contentment and resilience. See more on the characteristics of Thriving Adults here.

Natural pedagogy, learning through observation and apprenticeship from older members of the band, characterizes their lives. Even adults are guided by elder members of the band because the elders hold the wisdom, passed down through generations, of how to live well in that place and respect the natural world. We know from scientific studies that older people tend to be better at synthesizing information and taking into account the Whole. Overall, they develop human capacities that the western world has denigrated, many associated with right hemisphere functioning. One is polysemy, the orientation to and perception of a dynamic, fluctuating reality where things are wholly embedded in context and can be multiply identified. An aspect of polysemy that has also been dismissed by left-hemisphere-driven western culture is transrationality, awareness of nonpersonal, nonrational phenomena in the natural universe that does not readily fit into western notions of logic.

This evolved way of being in the world, documented among foraging groups, I call the cycle of cooperative companionship. Evolved nest provision buffers whatever genetic profile a youngster has, offering the support needed to optimize normal development. The well-functioning child becomes a well-functioning, still nested, adult. These nested, connected adults together maintain the cycle of cooperative companionship, providing for the basic needs of all.

The cycle we have all experienced moves in an almost opposite direction. The USA provides perhaps the worst-case scenario (a particularly tragic fact because it tends to export its practices around the world through the soft power of media, consumer products and advertising). In the USA, babies’ needs are minimized. For example, babies are often still treated in the perinatal period as if they do not feel pain. Neonates are traumatized by harsh medicalized practices (e.g., induced labor, bright lights, harsh touch, invasive smells, separation from mother, unnecessary vaccines, and circumcision). Parents watch medical personnel treat the baby this way, ignoring baby’s cries, and from this and the cultural myths about spoiling a baby, learn that they too can ignore the baby’s signals of distress. Of course, parents are also mistreated by societal practices, not offered significant family leave and support, and expected to raise the child on their own with little knowledge or practice of how to do so well.

Most of the evolved nest components are degraded or missing. Thus, the child ends up with a less-than-optimally-functioning neurobiology. Young children are coerced into what adults prefer (e.g., physical isolation, sleep training), because the culture promotes adult control and parents want to appear to be good parents. School children are coerced to do things they don’t want to do. When they have opportunity for freedom, they often don’t know healthy ways to use their freedom because they have not had practice and may not know themselves. They arrive at adulthood with deep wounds, distrust, resentments and grief.

These under-cared for adults typically remain unnested throughout their lives, struggling to work, raise a family and maintain a home. They can be easily manipulated by those who tap into their unmet desires (advertisers) and their fears (politicians). Their trauma is externalized onto ‘different’ others or their internalization is alleviated by various addictions. These adults are not only unable to meet the basic needs of the young, they don’t know how to create a culture that is connected and cooperative.

We know from animal studies that under-cared for daughters are worse as mothers than their own mothers. And so, a cycle of destructive, competitive detachment moves in a downward spiral, worsening over generations. We are there now. Our baselines for what we think is normal and good have shifted downward too (e.g., ‘it’s normal for babies to cry;’ ‘it’s normal for boys to be aggressive;’ ‘it’s normal for adults to be sickly and selfish;’ ‘it’s normal for a society to be a dog-eat-dog world’). Thus, we have reached a certain deadness of industrialized humanity. We have become robopathic instead of heartminded.

The harm done by a competitive detached culture involves not just human beings, who must enter various courses of therapies to undo the damage of an unnested childhood. Those who do not awaken to the destructive nature of their impulses and the larger culture will expand the damage to other societies (e.g., the USA and its allies have dropped on average 46 bombs a day on other countries for the last 20 years).

In a competitive detached culture, the missing capacities of connected empathy is even more extensive towards the natural world. Nature is perceived to be dangerous, dumb and inert and even full of pests deserving to be exterminated (this attitude was exhibited by European explorers and invaders and remarked upon by the natives of the lands later called the Americas). This is not our heritage either, as our ancestors lived in respectful partnership with the natural world.

We are at a point of shifting viewpoints and practices due to the many crises facing humanity. A return to a cooperative, companionship culture is needed and is being reawakened around the world. Not only do we need to be trauma-informed but wellness-informed. Wellness-informed practice entails understanding humanity’s basic needs and what brings about human thriving based on interdisciplinary scholarship, with an emphasis on the development and support of heart-mindedness and earth-centered-living knowhow.

My work at EvolvedNest.org and KindredMedia.org is intended to help return us to wise ways of living and being. Also see our new short film at BreakingTheCycleFilm.org.

References

Bowlby, J. (1969/1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books (Original work published 1969).

Bernstein, J. S. (2005). Living in the borderland: The evolution of consciousness and the challenge of healing trauma. New York, NY: Routledge.

Marvin Bram (2018) A history of humanity. Delhi: Primus Books.

Carter, C. S., & Porges, S. W. (2013). Neurobiology and the evolution of mammalian social behavior. In D. Narvaez, J. Panksepp, A. Schore & T. Gleason (Eds.), Evolution, early experience and human development: From research to practice and policy (pp. 132-151). New York: Oxford.

Champagne, F. (2014). The epigenetics of mammalian parenting. In D. Narvaez, K. Valentino, A. Fuentes, J. McKenna, & P. Gray, Ancestral Landscapes in Human Evolution: Culture, Childrearing and Social Wellbeing (pp. 18-37). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Cheverud, J. M., & Wolf, J. B. (2009). The genetics and evolutionary consequences of maternal effects. In D. Maestripieri & J. M. Mateo (Eds.), Maternal effects in mammals (pp. 11-37). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Diamond, J. (2013). The world until yesterday: What can we learn from traditional societies? New York: Viking Press.

Franklin, T.B., & Mansuy, I.M. (2010). Epigenetic inheritance in mammals: Evidence for the impact of adverse environmental effects. Neurobiology of Disease, 39, 61–65

Fry, D. (Ed.) (2013). War, peace and human nature. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Fry, D. P. (2006). The human potential for peace: An anthropological challenge to assumptions about war and violence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fry, D.P., Souillac, G., Liebovitch, L. et al. (2021). Societies within peace systems avoid war and build positive intergroup relationships. Humanities & Social Sciences Communication, 8, 17. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

Gowdy, J. (1998). Limited wants, unlimited means: A reader on hunter-gatherer economics and the environment. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Graeber, D. & Wengrow, D. (2018). How to change the course of human history (at least, the part that’s already happened). Eurozine, March 2, 2018. Downloaded from eurozine.com (https://www.eurozine.com/change-course-humanhistory/)

Graeber, D. & Wengrow, D. (2021). The dawn of everything: A new history of humanity. New York: MacMillan.

Hawkes, K., O’Connell, J.F., & Blurton-Jones, N.G. (1989). Hardworking Hadza grandmothers. In V. Standen & R.A. Foley (Eds.), Comparative socioecology: The behavioral ecology of humans and other mammals (pp. 341-366). London: Basil Blackwell.

Henn, B.M, Gignoux, C.R., Jobin, M., Granka, J.M., Macpherson, J. M., Kidd, J. M., Rodríguez-Botigué, L., Ramachandran, S., Hon, L., Brisbin, A., Lin, A.A., Underhill, P.A., Comas, D., Kidd, K.K., Norman, P.J., Parham, P., Bustamante, C.D., Mountain, J.L., & Feldman. M.W.(2011). Hunter-gatherer genomic diversity suggests a southern African origin for modern humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108 (13) 5154-5162; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1017511108

Hrdy, S. (2009). Mothers and others: The evolutionary origins of mutual understanding. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Ingold, T. (2005). On the social relations of the hunter-gatherer band. In R.B. Lee, R.B. & R. Daly (Eds.), The Cambridge encyclopedia of hunters and gatherers (pp. 399-410). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Krasnegor, N.A., & Bridges, R.S. (1990). Mammalian parenting: Biochemical, neurobiological, and behavioral determinants. New York: Oxford University Press.

Liu, W.F., Laudert, S., Perkins, B., MacMillan-York, E., Martin, S., & Graven, S. for the NIC/Q 2005 Physical Environment Exploratory Group. (2007). The development of potentially better practices to support the neurodevelopment of infants in the NICU. Journal of Perinatology, 27, S48–S74.

McDonald, A.J. (1998). Cortical pathways to the mammalian amygdala. Progress in Neurobiology, 55, 257-332.

Narvaez, D. (2014). Neurobiology and the development of human morality: Evolution, culture and wisdom. New York: W.W. Norton.

Narvaez, D. (2018). The neurobiological bases of human moralities: Civilization’s misguided moral development. In C. Harding (Ed.), Dissecting the superego: Moralities under the psychoanalytic microscope (pp. 60-75). London: Routledge.

Narvaez, D. (2019). Evolution, childhood and the moral self. In R. Gipps & M. Lacewing (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of philosophy and psychoanalysis (pp. 637-659). London: Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198789703.013.39

Narvaez, D. (2021). Growing, living and being rightly. In R. Tweedy (Ed.), The divided therapist: Hemispheric difference and contemporary psychotherapy (pp. 228-236). London: Karnac Books.

Narvaez, D., Four Arrows, Halton, E., Collier, B., Enderle, G. (Eds.) (2019). Indigenous Sustainable Wisdom: First Nation Know-how for Global Flourishing. New York: Peter Lang.

Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. New York: Oxford University Press.

Panksepp, J. (2010). The basic affective circuits of mammalian brains: Implications for healthy human development and the cultural landscapes of ADHD. In C.M. Worthman, P.M Plotsky, D.S. Schechter & C.A. Cummings (Eds.), Formative experiences: The interaction of caregiving, culture, and developmental psychobiology (pp. 470-502). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Perry, B. D., Pollard, R. A., Blakely, T. L., Baker, W. L., & Vigilante, D. (1995). Childhood trauma, the neurobiology of adaptation, and “use-dependent” development of the brain: How “states” become “traits.” Infant Mental Health Journal, 16, 271–291.

Power, C. (2019). The role of egalitarianism and gender ritual in the evolution of symbolic cognition. In T. Henley, M. Rossano & E. Kardas (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive archaeology: A psychological framework (pp. 354-374). London: Routledge.

Schore, A.N. (2019). The development of the unconscious mind. New York: W.W. Norton.

Sorenson, E.R. (1998). Preconquest consciousness. In H. Wautischer (Ed.), Tribal epistemologies (pp. 79-115). Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

Spinka, M., Newberry, R.C., & Bekoff, M. (2001). Mammalian play: training for the unexpected. Quarterly Review of Biology, 76, 141-168.

Suzman, J. (2017). Affluence without abundance: The disappearing world of the Bushmen. New York: Bloomsbury.

Suzuki, I.K., Hirata, T. (2012). Evolutionary conservation of neocortical neurogenetic program in the mammals and birds. Bioarchitecture, 2(4), 124–129..

Turner, F. (1994). Beyond geography: The Western spirit against the wilderness. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Wiessner, P. (2014). Embers of society: Firelight talk among the Ju/’hoansi Bushmen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(39), 14027-14035.

Yablonsky, L. (1972). Robopaths: People as machines. New York: Pelican.