By Mark Baumann, 2021

The attachment system is a survival system. It’s one of our many survival systems, similar to the fight-flight-freeze and larger polyvagal system. Perhaps one way those two systems differ is that attachment experiences have been found to have life span impact on patterns of human communication and information processing. One of attachment’s unique benefits is that the level of detail and significance of these patterns is much finer than provided by most other models describing human behavior and thought in the context of danger.

There are two primary models of attachment expanded from Mary Ainsworth’s ABC model, the ABC+D (or Berkeley) model, and the Dynamic Maturational Model of Attachment and Adaptation (DMM). In terms of using attachment assessments such as the Strange Situation Procedure or Adult Attachment Interview to understand the functioning of the attachment system, both models are quite similar. The DMM, however, differs in part by being more detailed, and offering a coherent, comprehensive and fully published model that nuances information processing biases. One distinction is the DMM’s focus on danger.

Basic DMM definition of attachment

Attachment involves a person who needs protection from danger and comfort, and a relationship with an attachment figure who can provide protection and comfort. The relational interplay between the person’s needs and the delivery of protection has an impact on the development of the person’s self-protective strategies, which include an array of behavior, communication, and information processing patterns.

Attachment is often considered only in terms of childhood experience. But humans need protection throughout life, so the attachment system is always in play.

Bowlby (1980) started his journey thinking about parent-child separation, and he ended his journey describing attachment as directly impacting information processing. He talked in terms of the defensive exclusion of unwanted information. He thought psychology’s many defense mechanisms were unorganized, and that attachment theory could organize them better. He was prophetic.

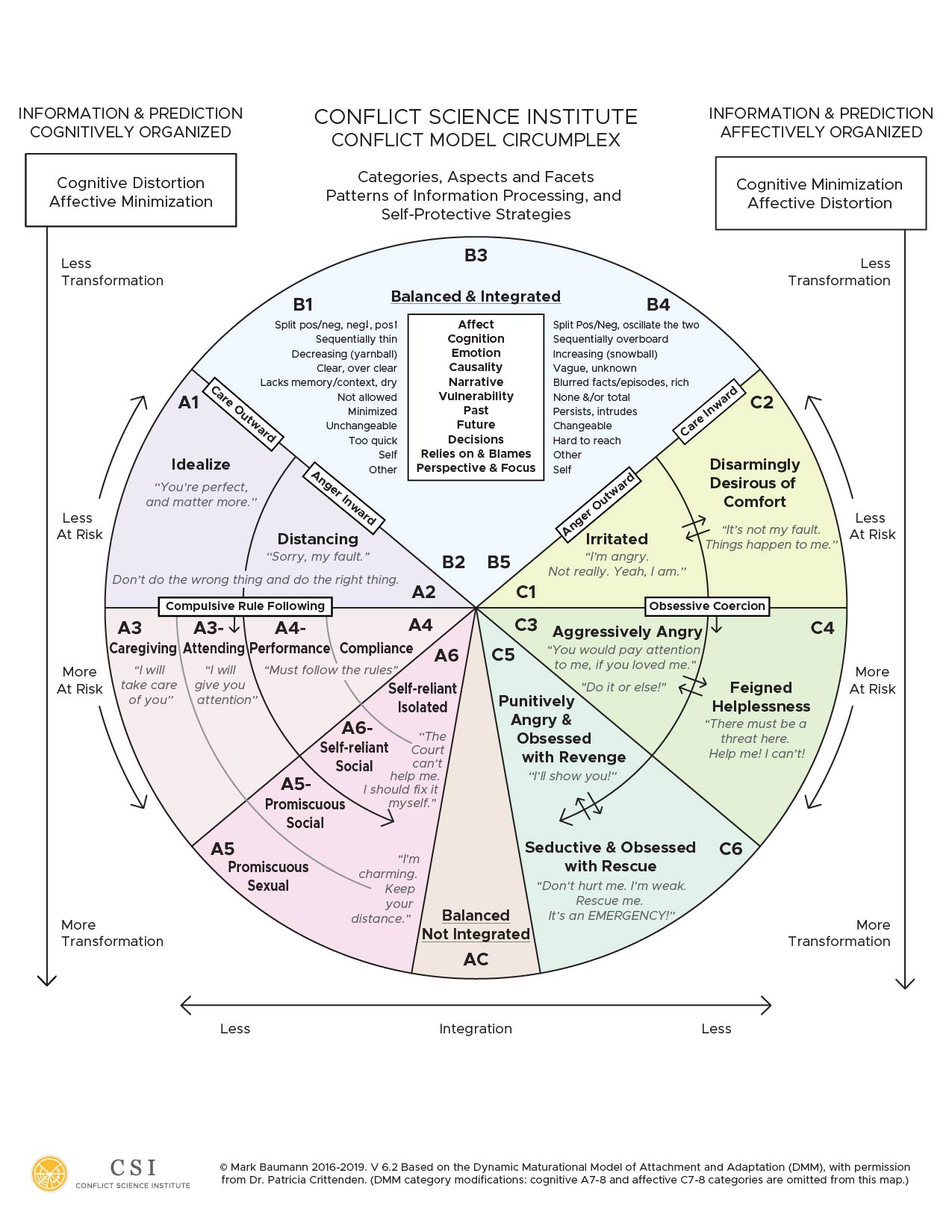

The Strange Situation Procedure primarily helped researchers tease out how children behave and communicate when they are put in a stress test (subjected to relational danger). The Adult Attachment Interview primarily teases out how adults think and communicate. Both assessments have confirmed Mary Ainsworth’s three basic attachment patterns, which she labeled as A, B, and C. You may know those as secure (B), avoidant/dismissive (A), resistant/ambivalent (C), or by other similar terms. The DMM uses the top-level terms balanced (B), cognitive (A), and affective (C).

Attachment researchers had identified a total of nine subcategories by the time Ainsworth passed away, and both the DMM and ABC+D models have now identified over 20 adult subcategories. The larger number of categories is a blessing and a curse, in terms of complexity. But, the DMM especially can be seen as robust, being helpful as a simple 3-part model and as a more complex model depending on your needs and available time to learn it.

Why three basic patterns in attachment theory?

The reason why there are just three basic patterns, according to the DMM, is because there are two primary sources of information that people can rely on to predict and survive danger: cognitive and affective. Those sources of information lead to unique and opposite patterns of protective strategies.

The cognitive A-pattern relies, to one degree or another, on external information which comes from experience of temporal sequences. Here are three examples of more intense sequences. All of these exclude certain types of information, specifically context and self-needs, and have incomplete narratives and conclusions.

“If I cry, my mom will get angry. Musn’t cry.”

“My mom is leaving this strange room. If I show my discomfort I will get scolded. I better not show my true feelings.”

“Immigration is a problem, people shouldn’t cross illegally, a wall will stop them, we should build a wall.”

The affective C-pattern relies, to one degree or another, on internal information, particularly the intensity of feelings. These examples also exclude certain types of information, such as rules and facts, and they too have incomplete narratives.

“When I get hungry, I need to cry until I get fed.”

“What’s up with this bizarrely lit and scary room with a ginormous mirror in it? My mom might leave me here, I never know, so I better stay vigilant. Oh jeez, she’s looking at the door and grabbing her purse… YIKES, there she goes, I can’t let her leave!! NO MOOMMMYYYY.”

“They’re pouring across the border, raping and murdering our woman and children! We must build a wall!!!”

The balanced B-pattern has access, to one degree or another, to both sources of information. Sometimes B-patterns utilize either information source primarily, depending on the circumstances.

“I live in Lithuania. The Belarusian government is deliberately dumping gobs of refugees on our border, and it’s a disaster! A fence isn’t perfect, but it will slow down the influx. We should consider putting up a reasonably priced fence, and then address the bigger problem.”

(Those are blog post-sized examples describing a complex topic.)

In terms of prevalence for helping professionals, the DMM and ABC+D research studies find both differences and similarities. In terms of information processing, most clients will be using A or C-like thinking. This is in part because B subcategories, in both models, involve patterns which are cognitive-oriented and affectively-oriented. More balanced B strategies for predicting and managing danger will often suffice such that they don’t need professional help. Thus, most clients seeking professional help will be both perceiving and processing danger from one or the other bias (cognitive or affective).

In terms of attachment, defining danger is interesting. What is relationally dangerous to people using A-strategies is the opposite for people using C-strategies. The DMM Danger List provides some examples.

A and C danger processing patterns are opposites

The DMM excels at bringing to light the many ways the two information processing patterns differ. Here’s a very short table to highlight some attachment-relevant aspects commonly seen in domestic violence cases and their opposite presentations.

| Common DMM attachment aspects and facets in light DV cases

|

||

| A – Obsessive compliance facet | Aspect | C – Compulsive coercion facets |

| Negative minimized/avoided, positive emphasized at expense of other needs even they are important. | Affect | Quick to display negative affect, oscillates between positive and negative affect displays. |

| Sequential but thin, if/then and “should” thinking. | Cognition | Sequentially overbroad, facts loose or unconnected. |

| Over-attributed to self. “It must have been my fault” | Causation | Causation unknown. “I didn’t do anything.” |

| Over-attributed to self. “I’ll take care of it.” | Responsibility | Avoided, others fully responsible. “NOW look what you made me do!” |

| Self-blame. “Sorry, it’s all my fault.” | Blames | Other-blame. “It’s all your fault.” |

| Self-reliant. “I don’t need help, I’ll fix it.” | Relies on | Other-reliant. “You need to fix this!” or “I can’t doooo it. Help me.” |

| Other perspective. “Let’s take care of your needs first.” | Perspective | Self perspective. “let’s take care of me first.” |

| Not allowed, minimized, irrelevant. “I don’t need a safety plan, we’ll be fine.” | Vulnerability | Invulnerable &/or total and flaunted. “They can’t hurt me!” or “They are trying to kill me! You have to help me!!” |

| Miminized, simplified semantic summaries. “It was pretty good really. I just need to move on with a divorce.” | Past | Persists and intrudes. “My spouse has been hounding me since day one, it’s never ending!” |

Using DMM attachment in client counseling

Clients often demonstrate clear patterns of information processing. Here are two common examples.

In my experience as a family law attorney, a large portion of survivors of domestic violence utilize cognitive self-protective strategies. These involve the minimization or denial of negative feelings and experiences, and the over-emphasis of positivity, which can lead to several issues. They may have difficulty recalling experiences and details of prior abuse. Conflict avoidance is a powerful motivator, which may put a desire to settle the case ahead of protecting their financial situation and children’s needs. They often say “I just need to have this case over with. My husband is a good dad, the kids will be fine.” However, after looking for and teasing out abusive behavior, it often becomes clear the father is just as harsh, controlling and abusive to the kids as he was to her. (Attachment is gender neutral so the genders here are just an example.) With help, parents can come to realize that they can find ways to lower their need to avoid conflict and raise attention to their own and their children’s needs.

For clients using C-strategies, they often relate stories with details that are connected by a common intense feeling, rather than by event or chronological order. Small problems often snowball into big problems. Their narratives are frequently blurry because they have poor temporal order. It may be hard to follow the story, or more importantly, to tease out what happened when, and what is the relevant fact leading to the big feelings. Trying to address the big feelings directly is often a lost cause. However, I can often optimize my client’s thinking by helping them put things in “good temporal order” by carefully examining the stories, asking for dates and building time lines with them. Asking for and organizing details about what led to the big feelings often clarifies what the real issue is. Once they can see their self-narrative clearly, it’s often a quick step to setting reasonable expectations and goals.

In all cases, to succeed in helping clients optimize their information processing, I need to approach them with mindsight principles, and as a transitory attachment figure who can provide protection.

Like IPNB, the DMM is a transdisciplinary model which clarifies attachment, and also incorporates many additional disciplines to understand how people have learned to function in the face of danger. The two models, DMM and IPNB, complement each other superbly. Attachment processing is similar to how people process information quite differently with a right or left-brain orientation. It’s also similar to the distinct fight-flight-freeze responses. By recognizing the information processing patterns in clients, professionals can help clients navigate a more balanced relational flow. The goal is integration.

For more information

The Wikipedia article on the DMM model offers a reasonably succinct overview with links to authorities and further reading. There are a series of articles on the Conflict Science Institute website which provide overviews and some case examples. My article titled It’s legal to harm children: Attachment healing in custody and domestic violence cases offers a case example of one way I used DMM attachment in my law practice.

Copyright Mark Baumann, 2021, with permission to MindGAINS.